Abstract: Advances in numerical simulation and multiphysics coupling techniques have provided deeper insights into the complex internal flow structures and noise generation mechanisms in valves, driving the development of highly efficient noise reduction technologies. This paper provides a systematic review of valve noise mechanisms caused by turbulent pulsation, vortex shedding, and fluid–structure interactions. The improvements in accuracy and the limitations of current numerical noise prediction methods are analyzed and compared. Additionally, recent advancements in noise control technologies are reviewed, covering passive methods such as structural optimization and acoustic treatment, as well as intelligent active control strategies. Future research should emphasize advanced multiphysics coupling simulations, deep learning–based modeling, and experimental validation methods to promote the development of low-noise and intelligent valve designs.

Valves are essential control components in industrial pipeline systems and are widely used in the petroleum, chemical, power generation, and shipbuilding industries, where they perform critical functions such as flow regulation, pressure control, and flow direction control. However, during operation, complex flow phenomena—including turbulence, flow separation, vortex formation, and cavitation—occur as fluid passes through the valve. These phenomena not only degrade valve performance and efficiency but also generate significant noise and vibration. Valve-generated noise not only pollutes the working environment and adversely affects the health and productivity of operators, but can also induce structural fatigue damage in valves and connected pipelines, potentially leading to serious safety incidents. As modern industries demand higher equipment performance and increasingly stringent environmental standards, valve fluid dynamics and noise control have emerged as critical research areas in engineering. Under extreme operating conditions—such as high pressure, high flow velocity, and high Reynolds numbers—the internal flow within valves becomes increasingly complex, and noise problems become more severe, placing higher demands on valve design and optimization. In recent years, rapid developments in computational fluid dynamics (CFD), computational aeroacoustics (CAA), and multiphysics coupling techniques, along with the extensive use of advanced experimental measurement methods, have significantly advanced research on valve flow characteristics and noise control. This paper provides a systematic review of recent research advances in valve fluid dynamics and noise control. Based on fundamental theories and mathematical models, this paper reviews the current understanding of internal valve flow characteristics, evaluates recent advances in valve noise generation mechanisms and control strategies, and highlights key challenges and directions for future research.

The motion of fluid within a valve follows the fundamental conservation laws of mass, momentum, and energy, which can be described by the following governing equations.

(1) Continuity equation

(2) Navier–Stokes equation

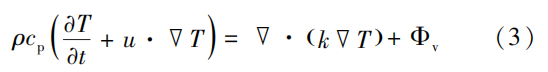

(3) Energy equation

In valves subjected to high-pressure differentials, the internal flow often behaves as a compressible fluid and is accompanied by complex phenomena, including shock waves, boundary-layer separation, and vortex shedding. Using a steam regulating valve as an example, when steam passes through the throat of the throttling region, its velocity can accelerate to supersonic levels, followed by rapid expansion and deceleration in the downstream section, forming recirculation zones and oscillating shear layers. During this process, part of the fluid’s mechanical energy is converted into acoustic energy, resulting in significant noise generation.

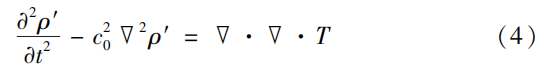

Valve noise primarily arises from three types of acoustic sources: monopoles, caused by volumetric flow fluctuations; dipoles, generated by unsteady forces on solid surfaces; and quadrupoles, resulting from turbulent stress fluctuations within the fluid. According to Lighthill’s acoustic analogy, fluid motion can be modeled as a distribution of equivalent sound sources, with the corresponding acoustic wave equation expressed as follows:

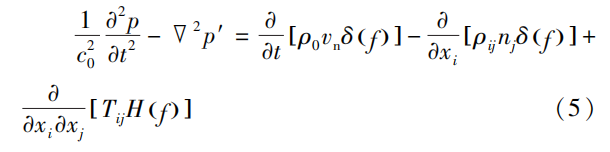

For practical valve noise prediction, the Ffowcs Williams–Hawkings (FW–H) equation is widely used, as it effectively handles moving boundary conditions. Its general form can be expressed as follows:

Here, the three terms on the right-hand side correspond to thickness noise (monopole source), loading noise (dipole source), and turbulence-induced noise (quadrupole source), respectively.

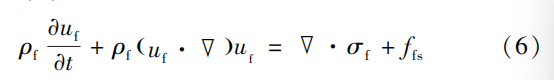

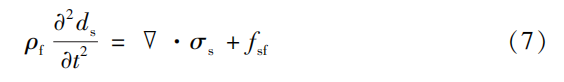

Valve noise is fundamentally a fluid–structure interaction (FSI) problem. Flow-induced pressure fluctuations excite vibrations in the valve body and internal components, which in turn modify the flow field, creating a coupled vibroacoustic feedback loop. The governing equations are expressed as follows.

(1) Fluid domain

(2) Solid domain

(3) Interface conditions

Research indicates that valve noise can generally be categorized into three types: turbulent noise, cavitation noise, and mechanical noise. Turbulent noise originates from pressure fluctuations caused by fluid turbulence within the valve and is primarily concentrated in the mid- to high-frequency range, while cavitation noise results from shock waves produced during the collapse of cavitation bubbles and spans a broad frequency spectrum. Mechanical noise is caused by vibrations and collisions among valve components and is primarily concentrated in the low-frequency range. Table 1 summarizes the primary sources of valve noise and their corresponding characteristics.

Table 1. Main Noise Sources and Characteristics of Valves

|

Sound Source Type |

Generation Mechanism |

Typical Frequency Range |

Dominant Operating Conditions |

|

Monopole |

Fluid volume pulsation (cavitation) |

1–10 kHz |

Liquid media with cavitation |

|

Dipole |

Surface force pulsation |

100–5000 Hz |

Low- to medium-pressure gas flow |

|

Quadrupole |

Turbulent stress fluctuations |

500–10,000 Hz |

High-pressure steam, supersonic flow |

|

Mechanical noise |

Component vibration and impact |

< 500 Hz |

Valve opening/closing, loosened components |

Valve opening has a critical impact on internal flow patterns. Research shows that at small openings (<30%), the fluid forms an “impinging jet” between the valve disc and seat, causing intense turbulent mixing and significant noise, whereas at large openings (>70%), the flow transitions into a “wall-attached jet.” Sun Kailang studied a ball valve, initially analyzing its steady-state behavior at fixed openings and then examining its dynamic response during transient opening and closing. The study revealed that increasing the inlet mass flow rate led to significant rises in both velocity and pressure fluctuation amplitudes at the valve center, while a decrease in the valve opening speed gradient resulted in reduced internal velocity gradients and lower flow-field turbulence. Studies on eccentric rotary valves in coal gasification plants have shown that vortex formation and turbulent pulsations are the dominant contributors to aerodynamic noise. Installing a noise-reducing orifice plate downstream of the valve lowered noise levels by about 9 dB, and further noise reduction was achieved by increasing the inlet pressure while decreasing the flow rate. For a steam vent valve in the chemical industry, vibration and noise issues were observed when the valve opening ranged from approximately 0% to 60%. Liu Baiqi et al. Liu Baiqi et al. conducted numerical simulations of the internal flow and acoustic fields at an actual operating condition with the valve 40% open. Their results revealed the presence of multiple vortical structures within the original valve design. The high-Mach-number regions within the valve internals and the orifice plate accounted for nearly 90% of the flow field, with localized supersonic flow zones. These conditions are highly susceptible to generating strong shock waves and associated tonal noise. Overall, existing studies indicate that internal flow characteristics differ significantly across valve types. Variations in pressure distribution, velocity, turbulence intensity, and energy dissipation within the valve are the primary contributors to valve noise.

With rapid advancements in computational technology, numerical simulation has become an essential tool for predicting valve flow behavior and noise. For instance, studies on marine three-way valves have achieved prediction errors as low as 1.85 dB. Valve noise simulation techniques have progressed from steady-state Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) approaches to high-fidelity transient methods, including Large Eddy Simulation (LES) and Delayed Detached Eddy Simulation (DDES). Conventional computational fluid dynamics (CFD) approaches, such as the RNG k–ε turbulence model combined with the acoustic Boundary Element Method (BEM), can effectively predict broadband noise characteristics and the distribution of sound pressure levels. Li Shuxun et al. applied an RNG k–ε model coupled with BEM to a high-pressure differential control valve and identified pressure pulsations in the throttling region of the valve body as the primary noise source. Structural parameter optimization reduced the overall sound pressure level to 51.02 dB. In the realm of multiphysics coupling, acoustic–fluid–structure interaction (AFSI) analysis has emerged as a key research focus. Wang Qigen et al. optimized the guide vane structure of a marine valve and conducted simulations combining LES with LMS Virtual.Lab. Their results demonstrated a significant reduction in sound pressure levels across specific frequency ranges and improved flow-field uniformity, highlighting concurrent benefits for both noise mitigation and hydraulic performance. Table 2 provides a comparison of commonly used numerical simulation methods for valve noise prediction.

Table 2. Comparison of Numerical Simulation Methods for Valve Noise

|

Method |

Computational Accuracy |

Computational Cost |

Applicable Scenarios |

|

RANS |

Low |

Low |

Preliminary engineering design |

|

LES |

High |

Extremely high |

Detailed acoustic mechanism studies |

|

DES / DDES |

Medium–High |

High |

Industrial optimization design |

|

FW–H Acoustic Analogy |

— |

— |

Mid- to far-field noise prediction |

Passive noise control technologies reduce valve noise by altering valve structures or adding auxiliary components. They are characterized by straightforward designs, high reliability, and ease of implementation. Table 3 presents a comparison of the noise reduction performance of different passive valve noise control technologies.

Table 3. Comparison of Passive Noise Reduction Technologies for Valves

|

Technology Category |

Noise Reduction Mechanism |

Typical Noise Reduction |

Additional Pressure Loss |

Applicable Scenarios |

|

Expansion and Pressure-Reducing Structure |

Stepwise reduction of flow velocity and energy dissipation |

6–8 dB(A) |

Negligible |

Liquid valve opening and closing |

|

Acoustic Lining |

Sound absorption and phase cancellation |

4–6 dB(A) |

None |

Steam valves |

|

Valve Sleeve Profile Optimization |

Suppression of flow separation |

1–4 dB(A) |

Positive or negative |

Small-opening control valves |

|

Noise-Reduction Orifice Plate |

Turbulence disruption and acoustic impedance mismatch |

8–10 dB(A) |

Significant increase |

High-pressure gas valves |

|

Active Control System |

Avoidance of resonant frequencies |

3–5 dB(A) |

None |

Intelligent control valves |

Structural optimization is the most commonly used approach for reducing valve noise, primarily involving flow-path profile optimization and the integration of damping structures. Studies show that a three-stage diameter expansion design—which produces a stepped pressure drop through the first annular passage (large cross-section) and the third pipe section (small cross-section), combined with sound-absorbing perforations in the inner liner and a double-layer sound-insulating outer wall—can reduce valve opening and closing noise by up to 15 dB. Acoustic treatment is another effective method for controlling the internal sound field of valves. By integrating acoustic treatment structures on the valve’s internal surfaces, sound reflection and absorption can be altered, effectively reducing noise levels. Common acoustic treatment techniques include the use of acoustic linings, acoustic resonators, and acoustic dampers. Multi-stage perforated plates are an effective passive noise control solution. Liao Jing et al. installed such plates downstream of an eccentric rotary valve, achieving a noise reduction of approximately 9 dB. Comparative studies of single-stage and multi-stage perforated plates indicate that single-stage plates are effective in the 500–1750 Hz frequency range, achieving a maximum sound power level reduction of up to 14 dB. In contrast, multi-stage perforated plates offer enhanced noise reduction in the 1000–4500 Hz frequency range, achieving a maximum sound power level reduction of up to 22 dB. Silencers are commonly employed to mitigate valve noise propagation. Depending on their attenuation mechanisms, they can be categorized as resistive silencers, reactive silencers, or impedance-composite silencers. Resistive silencers attenuate noise by absorbing acoustic energy through sound-absorbing materials and are mainly effective in controlling mid- to high-frequency noise. Reactive silencers reduce noise by reflecting and interfering with sound waves through changes in acoustic impedance, making them primarily effective for low-frequency noise. Impedance-composite silencers combine the benefits of resistive and reactive types, providing effective noise reduction across a wider frequency range.

Active noise control, an advanced technology, exploits the principle of destructive sound wave interference by generating secondary waves with equal amplitude and opposite phase to the primary noise, thereby effectively canceling unwanted noise. Compared with passive control, active noise control is especially effective at low frequencies and is not limited by the valve’s structural space. Table 4 presents a comparison of representative active noise control methods for valves.

Table 4 Comparison of Valve Active Noise Control Technologies

|

Control Method |

Technical Representatives |

Noise Reduction Bandwidth |

Real-Time Performance |

System Complexity |

|

Feedforward Control |

AFX-LMS Algorithm |

Wideband |

High |

High (Requires reference sensor) |

|

Feedback Control |

Wavelet Denoising |

Narrowband |

Medium |

Medium (Self-adaptive design) |

|

Harmonic Suppression |

PWM Frequency Optimization |

Specific Order |

Extremely High |

Low (Circuit-level implementation) |

|

Intelligent Drive |

IoT Drive System |

Mechanical noise across entire frequency band |

System-level |

High (Mechatronics) |

Despite these advances, the engineering implementation of active noise control still faces several challenges. The first is the real-time performance of control algorithms: advanced techniques such as AFX-LMS-CFPSO involve extensive matrix computations, which traditional DSPs find difficult to execute within sub-millisecond latency requirements. Second, under extreme operating conditions, strong vibrations can lead to sensor failure. Third, multi-source coupling poses a challenge: in large control stations, noise from multiple valves can interact, rendering conventional single-point control ineffective.

This paper presents a comprehensive review of research on valve fluid dynamics and noise control. Building on fundamental theories and mathematical models, it details the current understanding of internal valve flow behavior and systematically summarizes advances in valve noise control, covering noise generation mechanisms, numerical prediction methods, and control technologies. Analysis of existing studies indicates that, despite considerable progress, several challenges remain, including the accurate characterization of complex flow phenomena, a deeper understanding of multiphysics coupling mechanisms, and the development of more efficient noise reduction methods. Future research should focus on multiphysics coupling simulation techniques, the use of deep learning for valve noise control, the design of innovative low-noise valve structures, advanced experimental testing and validation methods, and the development of new materials and processes for noise reduction, thereby advancing the field of valve fluid dynamics and noise control.